A few years back, during one of my visits to Manila, I decided to go to Ayala Museum. This was right after one of their major renovations and I was curious to see what were the new additions to the museum.

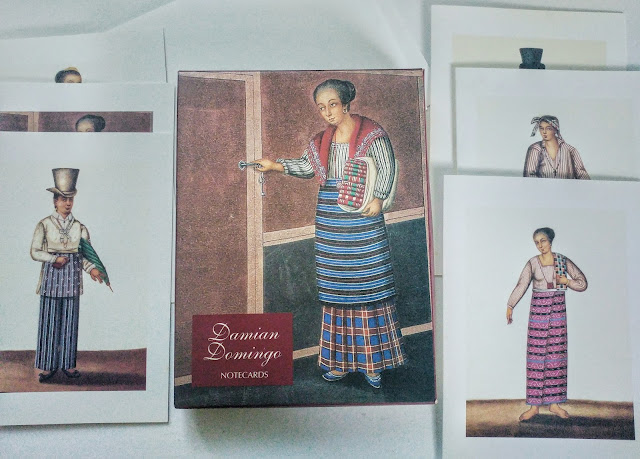

After touring the various exhibits, I went directly to the souvenir shop without any intention of buying anything. As I was browsing through the shelves, my attention was caught by the Damian Domingo notecards on display.

It was a bit expensive at that time. For a set of 12 notecards, I think it was about 300 to 400 Pesos which was the same price for the museum ticket.

But my investment has paid off. After a decade, the price of the notecards has doubled. My only regret was giving away three of those cards. I should have kept the entire set intact.

Who is Damian Domingo?

Frankly, I wasn't too familiar with Damian Domingo or his work during my visit to Ayala Museum. When we talk about Philippine Art in the 19th Century, we always refer to Juan Luna or Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo or even Simon Flores.

Born on February 12, 1796, Damian Domingo y Gabor was a mestizo de sangley (Chinese-Filipino). He established the first official Philippine Art Academy in 1821 in Tondo. Two years later, he was invited to be the director of Academia de Dibujo which was run by the Sociedad Economica de los Amigos del Pais.

He became an authoritative figure on the depiction of tipos del pais or coleccion de trajes which was a popular way of showing the different inhabitants of the country. The vibrant clothing or costumes of the different personages also differentiated those living in the cities or the provinces.

He was a sought-after portraitist of the Imperial Spanish Government, painting the official portraits of the Governor-Generals. He was also commissioned to paint Religious artworks.

Damian Domingo died young at the age of 38 years old. But his artistic influence resonated throughout the decades of the 1800s. The prominent artist, Justiniano Asuncion, trained under Domingo.

In 2010, Vibal Publishing came out with a coffee table book about Domingo, 'The Life, Art, and Times of Damian Domingo' by Luciano PR Santiago. The book also traces Domingo's modern-day heirs (e.g. Ongpins, Roas, Gabors, etc).

The following six tipos del pais were rendered on pith paper (a type of smooth, bone-white paper used for paintings) using Gouache (which is similar to watercolor). It has an opaque or matte finish to it.

Damian Domingo's creations laid the foundation for Western Art in the Philippines.

Living in the Philippines

To put everything in context, let's distinguish the people living in the Philippines during the Spanish Period. Clearly, there was a class distinction both racially and regionally.

Indio and India were used to identify the "Natives" or natural-born in the Philippines.

Mestizos were classified into several categories. There were the Mestizo de Espanol who has a mixed ancestry of Spanish and Indio. Mestizo de Sangley were those who had Chinese and Indio blood.

Tornatrás was a term used for those who had Spanish, Chinese, and Indio ancestry.

Tornatrás was a term used for those who had Spanish, Chinese, and Indio ancestry.

The term Peninsulares or Espanol were reserved for those who had pure Spanish blood. They were born in Iberian Spain.

Insulares or Filipinos were those of Spanish descent who were born in the Philippines.

19th-century #OOTD

My original plan for this blog post was just to have a short description of each painting but in the course of my research, I was able to unearth fascinating facts about how people dressed during that time; The significance of their clothes.

One of the results of my search is a paper written by Stephanie Marie R. Coo, Clothing and the Colonial Culture of Appearances in Nineteenth Century Spanish Philippines (1820-1896). It's a great read for those who are interested in learning more about this topic.

One of the results of my search is a paper written by Stephanie Marie R. Coo, Clothing and the Colonial Culture of Appearances in Nineteenth Century Spanish Philippines (1820-1896). It's a great read for those who are interested in learning more about this topic.

19th Century clothing was dictated by the norms of society. Costumes were also affected by where you live and the type of work that you do. Fabrics, designs, and even the construction added to the disparities.

Environment and climate are also factors in what people were wearing during those times.

Environment and climate are also factors in what people were wearing during those times.

Even in Jose Rizal's novels, clothing played an important role. The depiction of the class system was interwoven in the characters relationship with each other.

Domingo's tipos del pais is like the Instagram or Look Book of the Spanish Era. Aside from having varied clothes depending on the occasion, folks during this time are also known to socialize via a leisurely walk around the plaza or parks. These promenades are a way for them to show off their attire.

Una India Visayota, vestido de Gala c. 1830

|

| A Visayan woman in her best outfit |

In this painting of a Visayan woman's formal dress, she is wearing a simple designed square-necked, long-sleeved, collarless baro (dress) with folded cuffs.

An ankle-length patterned patadyong or patadiong worn as a wraparound skirt (similar to a Malong) was popular in the Visayas.

The combination of baro and patadyong might be classified as a pares or pair. One thing that bothers me is that the lady doesn't wear any footwear considering she's wearing her formal dress.

The combination of baro and patadyong might be classified as a pares or pair. One thing that bothers me is that the lady doesn't wear any footwear considering she's wearing her formal dress.

She is also seen with a pañuelo folded on her shoulder. A pañuelo was normally worn over the shoulders like a shawl. To complete the wardrobe, a scapular is worn around the neck to show her religious devotion. She's also painted wearing earrings.

Una Mestiza de Manila, vestida de Gala c. 1830

|

| A Mestiza woman in her formal wear |

Layering is the key for this Mestiza young woman. There are four essential pieces of clothing worn by the woman.

As we can see in the picture, she is wearing a long-sleeved baro with ruffled cuffs. A silk or lace panuelo is worn over it. Over her checkered saya, she has a striped saya (a two or three-paneled overskirt similar to an apron).

Her accessories include a peineta or panyeta, an ornamental comb; a pair of hoop earrings; a silk handkerchief with embroidery on the edges; a pearl or rosary beaded necklace with a religious medallion; and a dainty embroidered chinelas (slippers).

One tidbit that I've learned about wearing chinelas, is that wearers would normally have their big toes sticking out from the chinelas to keep it in place.

Una Mestiza Mercadera de Manila, c. 1830

In Domingo's portrayal of a Mestiza merchant, there is minimal difference in the pieces of costume that she is wearing in comparison to the Una Mestiza de Manila. The baro, saya, tapis, pañuelo, earrings, chinelas, and the medallion, all make an appearance.

Simpler in design but maybe more practical for her lifestyle as a businesswoman. Nevertheless, her station in life can be attested from the construction of her clothes. I like how she is shown carrying her ware (folded woven mat or it could be a blanket).

The material might be slightly different for the pañuelo. Her pañuelo is more of the sturdier fabric.

Simpler in design but maybe more practical for her lifestyle as a businesswoman. Nevertheless, her station in life can be attested from the construction of her clothes. I like how she is shown carrying her ware (folded woven mat or it could be a blanket).

The material might be slightly different for the pañuelo. Her pañuelo is more of the sturdier fabric.

Un Indio de Manila bestido de Gala, c. 1830

|

| A Mestizo gentleman |

Notice the several fashion influences in this gentleman's attire? Clothing for men was more of a fusion of the different styles available at that time.

Isn't the gentleman looked quite stylish as well as a dandy?

He's wearing his European felt or silk top hat at a jaunty angle; his sheer long-sleeved baro (a precursor of the Barong Tagalog) and sayasaya trousers are quite fetching. A white cravat adds flourish to the attire. His chinelas is more decorative than what we are normally used to.

Plus, he has his parasol tucked under his arm; a lighted cigarillo on his right hand and a white handkerchief on his left.

Untucked shirts were common during this time. The gentleman's baro has a high, folded collar and because of the diaphanous material used for it, an undershirt is needed. The length of the baro is almost similar to modern-day ones.

The sayasaya are embrodiered silk wide-legged trousers that were popular with the Mestizos and Indios during this time period. It could have been patterned after Chinese-style silk pants.

A silhouette of a religious medallion can also be surmised from the picture.

Un Yatteral de la Provincia de Bissaya, c. 1830

|

| A laborer's outfit |

A rendering of a working man by Damian Domingo. The subject seems to be a water seller because of his tapayan (earthenware jug).

The man's baro is shorter and looser than the formal wear seen in Un Indio de Manila. It also has a much lower neckline and comfortable sleeves which can be attributed to the material used.

The working man's salaual (trousers) are similar to the shirt which is short, loose, and wide. They would also roll-up their sleeves for practicality and convenience.

The man's potong or pudong, which can be used as a headwrap or a type of handkerchief that can be flung over their shoulders, reminds me of those old Filipino movies that featured albularyos or medicine men.

|

| "Estudyante Blues" |

I wonder how our generation would feel if they were required to wear this highly-formalized outfit to school every day. Aside from having a similar ensemble as the Un Mestizo de Manila, the young student pictured also has an identical outline with some variation.

During the 1820s to 30s, striped trousers were the norm. Given the transparency of their jusi or pina untucked baros, the striped design of their pants contributes to the elegance of their attire.

Instead of wearing the usual chinelas, he has chinelas masculinas or corchos which are slip-on shoes (the loafers of our times). These are made of velvet and embroidered. They're not usually made for walking. They're better suited for evening galas or formal parties.

During the 1820s to 30s, striped trousers were the norm. Given the transparency of their jusi or pina untucked baros, the striped design of their pants contributes to the elegance of their attire.

Instead of wearing the usual chinelas, he has chinelas masculinas or corchos which are slip-on shoes (the loafers of our times). These are made of velvet and embroidered. They're not usually made for walking. They're better suited for evening galas or formal parties.

Another trivia that I found out about footwear is that Filipinos of that bygone era would walk barefoot from point A to B and when they've reached their destination, they would wash their feet and then put on their chinelas before entering a place.

I would love to buy more of the Damian Domingo notecards or maybe own Luciano PR Santiago's book for my collection.

Damian Domingo's illustrations have brought us into the myriad lifestyles of the 19th Century Filipinos.

Comments